From "Leith" to the "Scotch" Baptists.

In the first quarter of the 19th Century, Sir Walter Scott, the novelist, produced one of his famous “Waverley Novels” - “The Heart of Midlothian” - where he more than once reflects on the religious climate of his homeland, always coming to the same conclusion, that “the air of Scotland” was “alien to the growth of Independency.” By Independency, of course, Sir Walter Scott and the Scotland that he spoke of generally meant anything that wasn't Presbyterian; and if any one has ever taken more than a casual breath of that air, they will know that the old author's dictum holds good – even up and until this present time. Of all the Independents, of course, there were none that the air of Scotland was more alien to then the Baptists, and the inhospitable nature of that air was to be easily detected at a very early stage. Whether or not there were actually any baptists, as such, in Scotland in the early days of the Reformation, is hard to determine. However, the position was clear for any who were, or for any who had notions of venturing into its borders. For as good John Knox was slaying the papacy with the words of his mouth he also had in reserve a few choice comments against that people who were then called “Ana-baptist”, and whom he declared to be, “Most horrible and absurd!” Well, be that as it may; but as we all too-readily know, it is very often those things that we consider “horrible and absurd” that have the horrible and absurd habit of persisting. And, in spite of the words of the old novelist – and the old Reformer, too – the baptist movement did manage to lift up its head, and even survive, in the “alien” air of the northern part of our United Kingdom.

As we have mentioned, there might have been, and probably were, those in the early days who had come to see the true nature of baptism as set out in the Word of God. However, as far as any organised groups or Churches of such people are concerned, the first beginnings of the baptist movement date around the middle of the 17th century and centre on the town of Leith which then lay on the outskirts of old Edinburgh. These were the days of the Commonwealth, of course, and when Cromwell had sent his Model Army north of the Tweed, many of those soldiers had carried with them the baptist convictions that they held dearly to their hearts. In 1653, then, we find “A Confession of Faith” being published in that town. It is a goodly document, and is reproduced, according to its title page, from “A Confession of Faith of the several congregations or Churches of Christ in London, which are commonly (though unjustly) called Anabaptists.” In all probability, this church at Leith was largely a garrison church; but for all that, it appears to have had an evangelistic spirit, as an old entry in a contemporary diary shows: - “This year,” it says, “Anabaptists daily increased in this nation, where never any were before. But now, many make open profession thereof and avow the same, and say that thrice in this week – on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, there were some dipped at Bonnington Mill, betwixt Leith and Edinburgh, both men and women of good rank. Some days there would be several hundred persons attending that action (of baptism) and fifteen persons in one day baptised by the Anabaptists.” This, too, was in the year 1653 the same year in which the Confession was published, but the same diary of eleven years earlier also mentions the name Anabaptist. However, in spite of the apparent evangelism and activity of those baptist soldiers at Leith and in other place, the baptist movement, as such, doesn't seem to have long outlived the departure of the Cromwellian forces. For the next hundred years almost, the “alien” air seems to have all but stifled that distinctive witness to the gospel which we call Baptist, and it is not until the mid-eighteenth century that there are stirrings afresh in the hearts of one or two enquiring saints who are to give new impetus to the cause.

The first name of the list is that of Sir William Sinclair of Keiss in Caithness, one of the most northerly shires on the mainland of Scotland. It is perhaps, somewhat out of keeping with what is to follow regarding the general conditions of the baptist in Scotland that the very first real “national” baptist church in the land should have been formed, and conducted its worship, within the walls of a castle! But so the providence of the Lord had ordained it to be, and on New Year's Day 1750 the church at Keiss was founded and constituted. Sir William Sinclair probably came under baptist convictions during his army career in the south, and as soon as he returned north again he began to make those convictions as widespread as possible. He was dubbed “the Preaching Knight” by the Bishop of the Diocese, who also

tells us that he was looked on as “a wrong-headed man confessedly by all who knew him.” This is a pretty sweeping statement, of course, and the basis of the charge of “wrong-headness” seems to lie in the fact that “he has taken up that odd way of strolling about preaching without commission or appointment of any man.” It was also said that he vented “the wildest and most extravagant notions that were ever hatched in the most disordered brain.” Some of Sir William's “notions” may, indeed, have tended to the extravagant; but it was that extravagance of zeal that very often accompanies the breaking forth of the truth of God upon a sincere soul. And, of course, there is nothing extravagant whatsoever in his “notions”, as they were called, concerning the right mode and subjects for Biblical baptism, or the proper observance of the Lord's Table, or indeed, the preparation of his little collection of Scriptural hymns – probably the first hymn book ever produced in Scotland for a non-conformist congregation.

tells us that he was looked on as “a wrong-headed man confessedly by all who knew him.” This is a pretty sweeping statement, of course, and the basis of the charge of “wrong-headness” seems to lie in the fact that “he has taken up that odd way of strolling about preaching without commission or appointment of any man.” It was also said that he vented “the wildest and most extravagant notions that were ever hatched in the most disordered brain.” Some of Sir William's “notions” may, indeed, have tended to the extravagant; but it was that extravagance of zeal that very often accompanies the breaking forth of the truth of God upon a sincere soul. And, of course, there is nothing extravagant whatsoever in his “notions”, as they were called, concerning the right mode and subjects for Biblical baptism, or the proper observance of the Lord's Table, or indeed, the preparation of his little collection of Scriptural hymns – probably the first hymn book ever produced in Scotland for a non-conformist congregation.

The church at Keiss, then, under the pastoral care of Sir William Sinclair - “the Preaching Knight” and “the wrong-headed man” - came into being and numbered around thirty at the time of his removal to Edinburgh where he died in the year 1768. He was succeeded to the pastorate at Keiss by John Budge, one of the members and probably an Elder of the congregation. This took place in 1763, the actual year of Sir William's departure from the north.

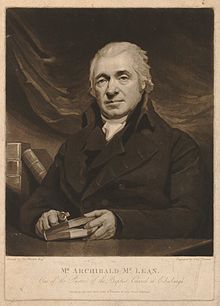

Now we may note that date – 1763 – for as the old founder of the first “home-bred” Baptist church in Scotland was preparing to leave, or had just left, his home in the northern county, another man by the name of Robert Carmichael, in Glasgow, set a question before one of his closest friends, Archibald McLean. “What do you think of baptism?” he asked him. And the results of the enquiries of both men into that question was the eventual founding of that grouping of churches that would become known as “Scotch Baptists”, one of the strongest arms of the movement in Scotland during those early days.

Both Archibald McLean and Robert Carmichael were members of the “Glas-ite” movement that had created a great deal of rumbling and division within the national Presbyterian Church of Scotland. (Carmichael was actually a minister of a Glas-ite congregation in Glasgow). John Glas had been a Presbyterian minister in the Church of Scotland, but had been “deposed from his living” in 1730 on account of his views on the church being separate from the State and independent of the State. “Christ's kingdom was a purely spiritual one,” he pronounced, and “a National Church (was) unwarranted under the New Testament.” He also held that “a society or church of believers was self-ruling.” It was these kinds of views, then, that Carmichael and McLean had already embraced. And it was as a follow on to those views concerning the nature of the church of Christ that the question of baptism within that church became a daily topic of conversation with them, and the subject of many letters between them after Carmichael went to take over a new charge in Edinburgh. Eventually, on October 9th 1765, Robert Carmichael was baptised in the public baptistry at John Gill's meeting house at the Barbican in London, and, on his return to Edinburgh, he baptised a few others who had embraced baptist views and had seceded from the Glas-ite church like himself. A similar train of events took place with Archibald McLean: he, with a few others, received baptism at the hands of Robert Carmichael, returned to Glasgow, and formed a branch of the parent church in Edinburgh.

Now, although McLean was the second of the two brethren in question to be baptised it was, nevertheless, his stamp that was to settle on the movement of the Scotch Baptists which followed. He was rightly referred to as “Father McLean” in that loving fashion that belongs to such titles, for he was the “father” of the Scotch baptist churches. McLean was a printer to trade, and he used the business under his control to good purpose, producing many first class works on the subject of baptism, and on other subjects doctrinal and practical. Mr Spurgeon makes mention of McLean's Commentary on Hebrews in his “Commenting and Commentaries,” and calls it, “One of the most judicious and solid expositions ever written.” And there is an interesting footnote on one of the pages of John Brown's Commentary on 1st Peter, reproduced by the Banner of Truth. John Brown is just about to make a quotation - “it is justly remarked by a judicious divine,” he says. However, as soon as he says that, he apparently feels inclined to inform us who this “judicious divine” is that he is about to quote, and in the footnote he gives us a little anecdote concerning him; “the late Archibald McLean,” he tells us, “from whose writings I have derived much advantage. It may be worth stating that when introduced to the late Robert Hall, one of the first things he said to me was, 'Sir, you have found me reading your countryman, Archibald McLean. He was a man mighty in the Scriptures, Sir; mighty in the Scriptures.'” Such was Archibald McLean; a man of no mean ability, and a man greatly revered in circles other than his own.

But what were his own circles? Who were the Scotch Baptists? Well, as far as their doctrine of the essential things of the gospel are concerned, they were in absolute accord with the other baptist churches that came into existence up and until the middle of the 19th century. That is, they were Calvinistic, holding to the truth of God's free grace in the salvation of sinners. However, it was in the realms of church “order” that the differences arose.

One of the strongest points of the Scotch Baptist system was the plurality of elders, or pastors, as they were also called, within each local church. These elders or pastors were men normally engaged in a daily job, but who took the oversight of the church between them outwith their regular working hours. On the other side of the divide stood the “English” baptists (of whom we shall hear in a later magazine). These “English” churches were not called English because they were composed of Englishmen, nor even because they had English pastors; but it was because these pastors were men set aside by the churches from their normal work for the work of the ministry, so following on in the general accepted pattern of the churches south of the border. But, for the Scotch churches, the plurality of the elders, was a cardinal doctrine in their scheme of church government. As churches grew, an elder was sometimes set aside, at least in part-time, over the care of the flock, but, strangely enough this was with regards to the pastoral oversight in visitation etc., and not in regards to the ministry of the word.

Alongside this view of the ministry, were some other features. These are listed in “The History of the Baptists in Scotland.” “The breaking of bread took place every Lord's Day and was for baptized believers only, and of those only such as held the same principles of faith and order; the prayers and exhortations of the brethren in the public meetings, the fellowship or contribution for the poorer brethren, the Agape or Love Feast were all scriptural institutions to be observed. Minor observances held as obligatory were sustained with a sober judgment, the kiss of charity, and the washing of feet, reserved for special occasions, were not regarded as religious institutes. It was the duty of a Christian to marry 'only in the Lord', and submission to the civil power in all things lawful, were prescribed.”

Such were the Scotch baptists; brought into being in the providence of God through those early remarks and conversations between Robert Carmichael and Archibald McLean in 1763. In spite of some set-backs and dissensions, there were about a dozen churches by the end of the century, making good and steady progress.

(In the next edition – the Brother Haldane etcetera)