The Brothers Haldane Etcetera

During the years that lay between those first questionings of Robert Carmichael and Archibald McLean concerning the matter of baptism, and the actual founding of the first Scotch Baptist churches, two brothers whose names must stand forever linked with the baptist witness in Scotland, were born into an old and noble Perthshire family. They were, of course, the brothers Haldane: Robert, born in 1764, and James his brother, four years later in the year 1768. And as the “Scotch” baptists had their antecedents in that which wasn't really baptist – that is, the Glas-ite movement – so the “English” baptists as they came to be called, and many who followed, likewise had their origins in a source outwith a determined baptist intention.

The Haldane brothers were members of the Church of Scotland which, at that particular point in the 18th century, was almost completely dominated by Moderatism. They were converted, and in 1797 James preached his first sermon and the die was cast for the work of a lifetime that lay ahead. Two aspects of the Haldanes' work have especial bearing on the direction that baptists were soon to travel. The building of the preaching Tabernacles in Edinburgh and Glasgow etc., accommodated some of the largest numbers ever gathered under one roof in Scotland to hear the gospel preached; while the founding of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel at Home, carried God's Word to as far-flung places as it had ever been carried in the life of the Church of Christ in the land. Out of both of these branches of the Haldane' work baptist churches were to spring and grow up until the Haldanes themselves eventually came to the acceptance of believers' baptism in the year 1808.

We may look at one particular case regarding the emergence of a baptist witness from a church originally founded simply on independent lines through the work of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel at Home. We quote from the History of the Baptists in Scotland: - “About the beginning of the 19th century Mr James Haldane, of Edinburgh, preached in the Grantown district. (Grantown-on-Spey, in the Spey valley, about 130 miles north of Edinburgh). Through the generosity of the Haldanes and others, several missionaries itinerated at intervals in the country, and their efforts resulted in the formation of an Independent church at Rothiemurchus. From Strathspey and Badenoch the Christians met in this church, with Lachlan Macintosh as their leader. He was a man of outstanding gifts and character, so that for years he continued to preach and administer the ordinances as an Independent largely supported the the Haldanes. Through study, he began to see the truth of believers' baptism, and being an honest man, he felt he must see Mr Haldane on this matter. He therefore walked all the way to Edinburgh (about 130 miles, remember) trusting that he would find his views overthrown by the greater experience of Mr Haldane. But the result of a long conference was exactly the opposite. Mr Haldane was absolutely shaken in his views and Mr Macintosh was confirmed in his, so that he was was baptised in Bristo Place church before returning north.” Has that kind of thing not so often happened? And then, we are told, “Shortly after this interview (the next month actually) Mr Haldane was also baptised.”

We may stay with Grantown for a moment, for it is a good story of a baptist witness coming to life and existence in those early days of the 19th century. Lachlan Macintosh returned north, of course, as the account tells us, and when he came back to his church he told them what had taken place and offered to resign from the place of Pastor. However, as it turned out, the majority of the church had also come to a baptist position, and it was simply a matter of baptising the members and re-forming the church as baptist, which was accordingly done.

Some time later, Lachlan Macintosh came into the actual town of Grantown-on-Spey itself. He was offered a room in a house to conduct some meetings, but it wasn't long before he was being cried down as an heretic by the local clergy, and the Laird – the Laird of Grant – issued a statement forbidding Lachlan Macintosh and his baptists to preach or meet in any house on his estate. The church, therefore, gathered together within the limited shelter of an old gravel pit on the outskirts of the town, and it was to this gathering that a young man by the name of Peter Grant was one day drawn to hear the words of everlasting life for the first time.  Peter Grant was to become one of the shining lights of the baptist witness in Scotland, and in 1826 he was appointed pastor of the church of his conversion, a charge which he faithfully held for the next forty-one years. Before his conversion at the baptist meeting at the gravel pit he was the Precentor and leader of the praise in the Parish church, where he used to conduct the worship with his fiddle, and was accustomed, as he later said, to hearing many sermons from the daily newspaper, which the minister used to refer to as “old boney”! During Peter Grant's ministry, the congregation grew to around three-hundred and by that time were able to hold their services in various premises. However, a permanent meeting-place was desirable and a site was applied for to the Earl of Seafield who then seems to have been in possession of the Grantown estates. In the tender providences of God he granted them a site, and it turned out to be no other spot than the old gravel pit on the outskirts of the town where they had so often weathered the storms, both of nature and persecution.

Peter Grant was to become one of the shining lights of the baptist witness in Scotland, and in 1826 he was appointed pastor of the church of his conversion, a charge which he faithfully held for the next forty-one years. Before his conversion at the baptist meeting at the gravel pit he was the Precentor and leader of the praise in the Parish church, where he used to conduct the worship with his fiddle, and was accustomed, as he later said, to hearing many sermons from the daily newspaper, which the minister used to refer to as “old boney”! During Peter Grant's ministry, the congregation grew to around three-hundred and by that time were able to hold their services in various premises. However, a permanent meeting-place was desirable and a site was applied for to the Earl of Seafield who then seems to have been in possession of the Grantown estates. In the tender providences of God he granted them a site, and it turned out to be no other spot than the old gravel pit on the outskirts of the town where they had so often weathered the storms, both of nature and persecution.

What was taking place, of course, in the “country” districts, as we might call them was also being evidenced in the cities themselves through the Tabernacles. As various members, elders, and ministers within the Tabernacles, as well as within the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, began to search the scriptures, and they began to see more and more clearly that, “If thou believest thou mayest be baptised.” And so, with the expulsion of such people from the Tabernacles, prior to the Haldanes themselves becoming baptists, there were laid the first foundations of those churches that would come to be known as “English”, on account of their practice of calling a single minister to be appointed full time over the charge of God's flock in any particular place. Among the names most associated with this particular branch of baptist work in Scotland are men such as Christopher Anderson, George Barclay, Dr. Innes, and so forth.

One of the features common to all the Scottish baptist churches at this time, from whichever quarter they came, was their great interest in the new-found missionary movement that had come to the fore under Carey and Fuller. Archibald McLean had gone thoroughly into the question of why the gospel should be spread among the heathen abroad, and in 1795 delivered one of the most stirring papers on the subject. In the same manner, the “English” churches leaned very heavily to the obligation of missionary enterprise, and it was in this direction that Christopher Anderson first felt inclined immediately after his break with Haldane Tabernacle in Edinburgh. He had a strong desire to join up with Carey in India, but health reasons forbade this, and so, he set about endeavouring to establish a baptist witness other than the existing “Scotch” baptist system. Andrew Fuller freely confessed his great admiration for Christopher Anderson, and announced that he would gladly “divide” his income with him if he would come south and work alongside him in his pastoral and missionary labours.

Much the same kind of thing can be said of George Barclay, another of the new emerging baptists who had outpaced the Haldanes in the understanding of the scriptural nature of baptism. The Haldanes had started schools for the training of their pastors and evangelists. This immediately set them apart from the older Scotch baptists, and when the “Haldane men”, such as Anderson and Barclay withdrew from the Tabernacles etc., they weren't attracted to the “Scotch” system and so, set about founding their own churches along the “English” line of settled, full time ministers. George Barclay's church was begun in Kilwinning in Ayrshire in December 1803, moving in a few years time to Irvine, not far away. They at first met in an upper room in the town, and for the next thirty-six years George Barclay continued as pastor of the flock, adding over two hundred members to the church during his pastorate. His love for the work of mission abroad is, perhaps, typified in the name of his youngest son whom he named William Carey Barclay, and we may assume a great deal of spiritual pleasure in the Ayrshire pastor when that same son eventually went out to join Carey in Serampore as a printer and translator in the work.

But so the work of the baptist testimony went on. The initial years were painfully slow and very much uphill. After thirty years of labouring in the work – from 1765 to 1795 – Archibald McLean reckoned there to be about four-hundred baptists throughout Scotland. By the middle of the 19th century, however, there were an estimated 90 churches containing about five-and-a-half thousand members. The old “Preaching Knight” of Caithness, although far from being complacent would, no doubt, have rejoiced in the changed circumstances from that New Year's Day in the middle of the previous century when he had opened the vaulted room of his castle at Keiss to conduct the worship of God after the manner known as baptist.

There is just one more thing we might mention to conclude this part of our review – one more person, really. How much could be said of the Haldanes and their influence, not only on the baptist witness which came out of their work, but on the whole religious scene in the country. To that spiritual climate that had begun to settle in may parts must be attributed the impetus that brought about the Disruption of 1843 which saw the Free Church of Scotland coming into existence. Of the two brothers, James was, perhaps, the more able preacher and he never tired of declaring that great reformation doctrine of Justification by faith alone. The influence of Robert is particularly marked in such things as his work among that band of young men in Geneva – The Monod brothers and Merle D'Aubigne etc., his great Commentary of the Romans, and his massive defence of the Text and Canon of the Scriptures, which John Macleod in his Scottish Theology calls, “The crowning work of Robert Haldane's life.” So much could rightly be said.

But mention must be made of Sinclair Thompson; a man much less known than either of the Haldanes, and, indeed, less known than a good many other baptists of his day, and yet, a true baptist pioneer for all that.

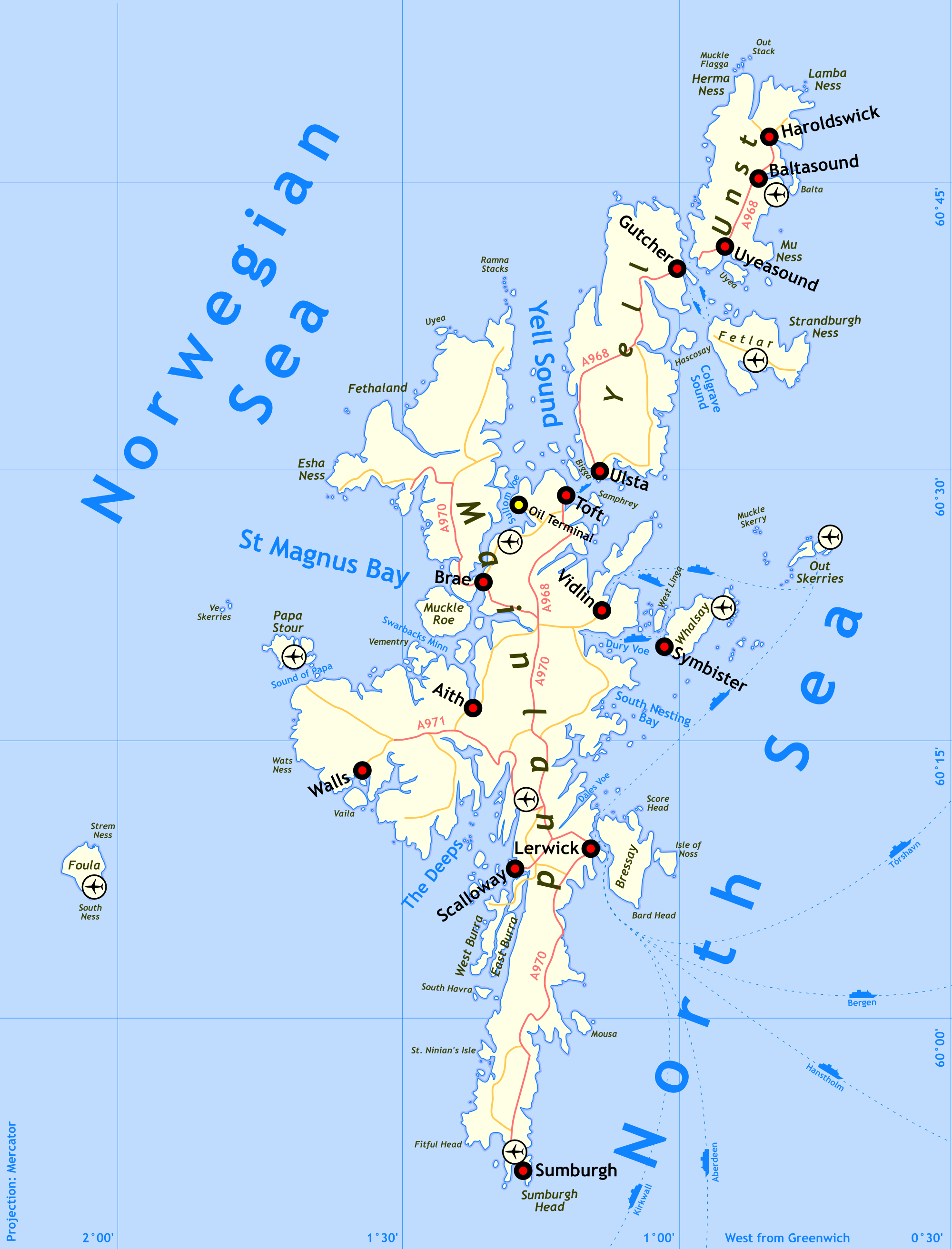

Sinclair Thompson lived in the Shetland islands, and through his reading of God's Word he became absolutely convinced that baptism entailed “Much water, and believers only.” He had never so much as heard that there were such people as baptists, but when he learned of the existence of some in Edinburgh he set out by boat on a few occasions (but was always hindered by weather etc.) to sail down from Shetland to be baptised, at their hands. God obviously had another intention, for eventually a baptist pastor came on holiday to Shetland, Sinclair Thompson was baptised, and there was soon formed the first baptist church under his care on the Islands. We say the first, for during Thompson's forty-eight years of ceaseless toil around the Shetland group he formed seven churches in all, and it is estimated that he preached over six thousand sermons in his travels. He surely earned the title, “The Shetland Apostle”. He died in 1864 in his 80th year, an unapologetic Calvinist to the end. “Do you doubt whose is the work in the work of salvation?” he challenged, “ A careful perusal of the first chapter to the Ephesians will show the origins of all the real conversions that have taken place, or ever shall take place, upon this earth.”

Sinclair Thompson lived in the Shetland islands, and through his reading of God's Word he became absolutely convinced that baptism entailed “Much water, and believers only.” He had never so much as heard that there were such people as baptists, but when he learned of the existence of some in Edinburgh he set out by boat on a few occasions (but was always hindered by weather etc.) to sail down from Shetland to be baptised, at their hands. God obviously had another intention, for eventually a baptist pastor came on holiday to Shetland, Sinclair Thompson was baptised, and there was soon formed the first baptist church under his care on the Islands. We say the first, for during Thompson's forty-eight years of ceaseless toil around the Shetland group he formed seven churches in all, and it is estimated that he preached over six thousand sermons in his travels. He surely earned the title, “The Shetland Apostle”. He died in 1864 in his 80th year, an unapologetic Calvinist to the end. “Do you doubt whose is the work in the work of salvation?” he challenged, “ A careful perusal of the first chapter to the Ephesians will show the origins of all the real conversions that have taken place, or ever shall take place, upon this earth.”

Such were the baptists in Scotland by the year 1850 – a hundred years on from Keiss, two-hundred years on from Leith, and still standing in the same Free Grace tradition set forth in the old Confession of Faith published in that town. In those early eighteen hundreds there was only one non-Calvinistic baptist church in the whole of Scotland. By nineteen-fifty, however, the situation had completely and entirely reversed, and a Calvinistic baptist church, as such, was virtually an unknown structure in Scotland. Individuals there were, no doubt, who still rejoiced in the faith of their founding fathers, but as far as baptist church life was concerned there was much similarity between the “old” and the “new” as there is between the proverbial “chalk and cheese.”

(Next edition – 1850, And After)