Believing that the time had now come for him to enter another “vineyard” under the direction of the Lord, William Burns once again cast a wistful eye to the great land of China. The days of the awakening in Scotland prior to the Disruption now seemed to have subsided somewhat, and with the need tending more to pastoral ministry, the place of Burns, who had traversed the land bringing revival in his wake, called for consideration before the Lord. He diligently sought the mind of the Lord in every available means, and at the end of his search ascribed all to the confirmation of the Lord's direction: “To sovereign grace be the praise,” he wrote, “the endless, unutterable praise.”

The tremendous uprooting involved in moving from the one sphere of labour in “The Land of the Covenant” to the endless miles of the “Mystic East” might have caused a lesser mortal to have shrunk back into the exit of unsuitability; but Burns was undaunted. “The study of Chinese,” he was told, “requires bodies of iron, lungs of brass, eyes of eagles, hearts of the apostles, memories of angels, and lives of Methuselah.” He proved he had all of these in just proportion. “When would you be ready to leave for China?” he was asked by the Mission Board that interviewed him; “Tomorrow,” was the curt reply.

It wasn't quite like that, of course, and even the few available ships that travelled to Hong Kong were subject to the winds and the waves of the Lord's disposing, and it was two months before William Burns set sail from Portsmouth for the land of the Lord's choosing for him. He was just about to walk into the Scotch Church, Woolwich, to conduct a farewell service when the word arrived that the Mary Bannatyne was ready to leave Portsmouth next morning. He rushed to the railway station, but missed the train to Portsmouth; returned to the church, committed all into the hands of the Lord; preached his sermon, and on arriving at Portsmouth next morning discovered that the sailing had been held up! So, in November 1847, he arrived in the harbour of Hong Kong.

Like so many missionaries before and after him, William Burns experienced that Holy restiveness that continually urged him away from the relative comforts of the great sea ports where so many other missionaries and white people in general had  congregated, and after about fourteen months of study in the Chinese language he felt that the time had come for him to move off across the narrow strip and on into mainland China. “You desired that three doors might be opened to me,” he wrote home to his mother, “the door of utterance into the language; the door of access into the country of China; the door of admittance for the Lord's truth into men's hearts. The first of these has been opened in an encouraging degree already; and it now remains to seek by prayer and action that the other two doors may be opened also.” They were, indeed, to be opened, but, as William Burns soon discovered, those eastern hearts had been locked up tight for so long with the devil's bolts that many assaults would be required before the final breach could be made.

congregated, and after about fourteen months of study in the Chinese language he felt that the time had come for him to move off across the narrow strip and on into mainland China. “You desired that three doors might be opened to me,” he wrote home to his mother, “the door of utterance into the language; the door of access into the country of China; the door of admittance for the Lord's truth into men's hearts. The first of these has been opened in an encouraging degree already; and it now remains to seek by prayer and action that the other two doors may be opened also.” They were, indeed, to be opened, but, as William Burns soon discovered, those eastern hearts had been locked up tight for so long with the devil's bolts that many assaults would be required before the final breach could be made.

He moved off into Canton, and so hard was the work here that William Burns felt hard pressed in making his own calling and election sure. His letters home at this time provide valuable material on the trials of a good missionary of Jesus Christ; how much he needed the Lord in that Christless atmosphere: “What need I have of the Lord of the Sabbath in a Sabbathless land like this,” he wrote, “Oh, that I may not lose my own soul in seeking to save the souls of others.”

The work in Amoy proved to be more fruitful, even though the hearts of the people were as initially hard as those that Burns had encountered in Canton. In Amoy he reckoned that there were six-hundred opium smoking dens, and remarked on how the habit showed itself on the very faces of the men and women of that place. In spite of this, however, the Word of the Lord began to penetrate, and in due course there came the day of great rejoicing when seventeen souls were baptized and formed into the first believing church under the great Scots preacher.

Had any of the congregations of Scotland to whom Burns had ministered during those windswept days of revival come across the great Scottish minister now, it is doubtful if they would have recognised him. Burns had begun to attire himself with the dress of the Chinese to whom the Lord had sent him with the gospel. He had come into contact with Hudson Taylor and both of them had deemed it essential not to show any marked difference in outward things between themselves and the people of the land. One might get away with European dress in the large towns, Burns observed, but one must discard it in the interior or else, “… be gazed at like a gorilla, or an orang-utan!”

The association of Burns with Hudson Taylor was especially blessed to Burns in the work that they entered into in the town of Swatow. A Christian sea captain by the name of Bowers spoke at a prayer meeting in Shanghai when the two men were present, and told of the evil running rampant in that place. After the meeting, the captain exhorted both Burns and Taylor to lay the responsibilities of Swatow upon themselves; “If traders of all nationalities can live there,” he told them, “why should not ministers of the gospel?” The two friends were in silence as they returned to their lodgings, but shortly afterwards, Taylor came to Burns and told him that he knew the Lord was directing him to Swatow, but kept holding back because he did not want to part with Burns. But the burden had been laid just as heavily upon the Scot; “This very night,” he told Taylor, “I have accepted the call to Swatow, my only regret being that I realised that it would mean that we must part.”

The only accommodation available to the two friends in Swatow was a single room above an incense shop! This they accepted as the Lord's provision. The groundwork was hard, and eventually Hudson Taylor had to leave the town for medical care, hoping to return as soon as possible; in fact, they never saw one another again. Burns encountered more obstacles in this branch of his work than in any other, but through the Lord's grace learnt to overcome these and witness a good confession before men. On one occasion he was arrested and told to bow before the chief magistrate; “Your Excellency,” he told him, “I will render to you the same obeisance as I would to my Sovereign Queen Victoria, humbly on a bended knee, but I will only kneel on both knees to God, the King of Kings.”

But, in spite of the hardness of the soil, and the heat and the toil of the day, the blade and the ear of the work in China began to show through.  One of the things that rejoiced the heart of Burns more than anything else was the inauguration by the Amoy church of its own home missionary society; the Chinese church was now turning, unaided from outside sources, to evangelise her own land.

One of the things that rejoiced the heart of Burns more than anything else was the inauguration by the Amoy church of its own home missionary society; the Chinese church was now turning, unaided from outside sources, to evangelise her own land.

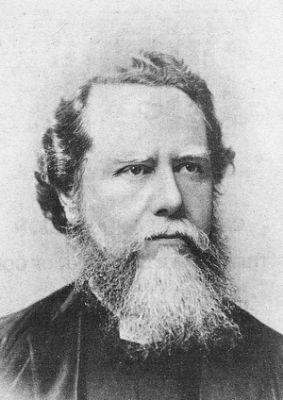

The days of William Chalmers Burns were now drawing to a close, and after a full life to the glory of the Lord, he died in April 1868.

Contrary to the Chinese practice, he ordered that no new clothing was to be bought for his dead body when he passed on, and his few belongings that were brought home after his death showed that he was rich only in those things of another land: “A few sheets of Chinese paper, a Chinese and an English Bible … a single Chinese dress, and the blue flag of his gospel boat.”

| This Page Title – William Chalmers Burns (Part 2) The Wicket Gate Magazine "A Continuing Witness". Internet Edition number 93 – placed on line November 2011 Magazine web address – www.wicketgate.co.uk |