One of the difficulties in trying to deal with something of the life of George Whitefield is the uniqueness of the times in which Whitefield's life was set. He was born in Gloucester in the early part of the eighteenth century, and it was that century that was to see one of the greatest revivals of religion that the world had probably ever seen since the very days of Pentecost itself.

The very term “Revival of Religion” appears to have sprung from that period, and seems to have been first coined by the greatest of all the American theologians, the mighty Jonathan Edwards. He it was who ministered in that small town of Northampton in the historically Puritan state of New England, where, it was said in those days, that to ride through the very streets of that town as a passing stranger was but to invite the outpouring of the Holy Spirit of God upon your head in converting grace and power. It was Edwards who stood with a lighted candle in one hand, and his massive theological sermons in the other, simply “reading” the words that he had before prepared and written, until the people in his church grabbed hold on their pews “lest they should tumble into hell at that very moment.”

And what was true of Edwards at Northampton was also true of many other parts of America, and of England, and of Wales, and of Scotland, too – of Cambuslang, and Kilsyth, where the glory of the Lord was seen, and the windows of heaven were, indeed, opened up, and the blessings of the Lord poured out on many waiting heads. As far as “names” go, as well, there is hardly another period of the Church so rich in such a variety of men and women of tremendous stature in the things of the Lord: The Countess of Huntingdon and Lady Glenorchy, John Newton and Augustus Toplady, William Cowper and old John Berridge, Henry Venn and James Hervey, William Girmshaw and William Romaine, and the Welsh brethren – Daniel Rowlands and Howell Harris. Relatively speaking, “a multitude that no man can number.” So, when it comes to looking at the life and work of this man George Whitefield it must be remembered that these were the kind of days in which he ministered the gospel, and these were the kind of people with whom he ministered the gospel, for the word of the Lord ran, and had free-course, and was glorified in those days.

And yet, in spite of the uniqueness of those days and the men of the times, the man George Whitefield seems to stand out head and shoulders above any of the rest for absolute ability and usefulness, and labour and work in the things of the gospel. Whitefield has been largely forgotten in our day, but if we look to some of the testimonials of the men and women of Whitefield's own day we see that they all concur in giving him the chief place among those who laboured in that outstanding age. “Many have done valiantly,” they all say of him, “but he has excelled them all.”

John Newton:

“As a preacher, if any man were to ask me who was second best I had ever heard, I should be at some loss; but in regard to the first, Mr. Whitefiled so far exceeds every other man of my time that I should be at no loss to say.”

William Cowper, the poetic recluse of Olney:

“Paul's love of Christ, and steadiness unbribed,

Were copied close in him, and well transcribed;

He followed Paul; his zeal a kindred flame,

His apostolic charity the same.”

John Wesley:

“Have we read or heard of any person who called so many thousands, so many myriads of sinners to repentance.”

Henry Venn:

“… if the greatness, extent, and success of a man's labour can give him distinction among the children of Christ, than we are warranted to affirm that scarce any one has equalled Mr. Whitefield.”

One of Whitefield's keenest supporters was the countess of Huntingdon, a woman who “laboured with him in the gospel.” With the wealth that she believed to be given her by the Lord she built numerous chapels for the preaching of the evangelical gospel, and built into many of these chapels were what she was pleased to call the “Nicodemite corners.” These were areas, curtained off from the pews where the “religious leaders” – the non-evangelical Bishops etc. – could sit and listen to the word of regeneration. One such Bishop – the man who ordained Whitefield to the ministry – believed that her Ladyship had become “righteous overmuch” and expressed the opinion that he had been mistaken in ordaining the man Whitefield in the first place; “My Lord, mark my words,” she countered to the defence of Whitefield, “when you are on your dying bed that will be one of the few ordinations you will reflect upon with complacency.” The “prophecy” had a practical fulfilment when, as a dying gesture the Bishop sent £10 for the work.

Even outwith his own age, the testimonies to Whitefield's influence and stature abound; Murray McCheyne wrote in his diary, “Oh, for one of Whitefield's weeks in London,” and Spurgeon unashamedly announced him as his preaching pattern from his earliest days: “My own model is George Whitefield,” he says, “but with unequal footsteps must I follow in his glorious tracks.”

This, then, in brief, is something of the man George Whitefield, and of the times in which he preached to gospel. However, it does well to remember that the days in which Whitefield preached were far-different from the days in which he was born in 1714. J.C. Ryle summarises the general religious climate of that time, “From about the year 1700,” he tells us, “till about the era of the French revolution, England seemed barren of all that is really good … Christianity seemed to lie as one dead, insomuch that you might have said ‘She is dead.’ Morality, however much exalted in pulpits, was thoroughly trampled underfoot in the streets. There was darkness in high places and darkness in low places – darkness in the court, the camp, the parliament, and the bar – darkness among rich and darkness among poor – a gross, thick, religious and moral darkness – a darkness that might be felt.” We do well, as we have already said, to bear this “state of things” in mind. There is a great tendency among the professing people of God to assess the situation of their own day, pronounce it to be the worst times that ever there were and then, hide behind the fact that it must be near “the end”, and fail in their responsibility to be faithful witness in their own generation. A glance at the history of the church of Christ on earth will quickly show us that the Church has been called to pass through troubled and evil times before, and yet, God has been pleased to revive her in the very “midst” of those years. Whether revival, or quickening, or true reformation is in the mind of a Sovereign God for this age, we have no way of determining; however what our God may be pleased to do is a question that must stand separate from what He has committed His Church to do in every generation, and that is, be faithful unto Him and spread the gospel.

So, then, George Whitefield was born into such a day; and he was born into such a place as a pub! The Bell Inn in Gloucester first heard the voice that was to call many to repentance. It had been run by his father, but when he died in Whitefield's second year the responsibility fell on the mother, and in another few years Whitefield himself was pressed into service; “I began to assist in various ways,” he tells us, “until at length I put on my blue apron and washed mops, cleaned rooms, and, in a word, became a professed and common drawer for near a year and a half.”

He tells us something of those early days: he had a very retentive memory, and, whereas, some would look on this as a blessing, he was keenly aware of the dangers of it, for there were many old “stories” and expressions that he found difficult to rid his mind of in later years. He had a great capacity to mimic and would act the preacher on many occasions. He was also impressionable, and followed the trends of his day; “I got acquainted,” he tells us, “with such a set of debauched, abandoned, atheistical youths that if God, by His free grace, had not delivered me out of their hands, I should long ago have sat in the scorner's chair. I took pleasure in their lewd conversation. My thoughts of religion became more and more like theirs. I affected to look rakish, and was in a fair way of being as infamous as the worst of them.”

The intervention of God's “free grace”, however, was becoming apparent, and even before Whitefield left Gloucester for the University at Oxford religious thoughts were beginning to form themselves in his mind. These, of course, as is so often the case, expressed themselves in a severe and outward self-righteous approach to God, and, he tells us himself, as he had been so impressed by the bad company that he had earlier kept, so he was now completely swept overboard by his new turn of life, being much under the influence of the Wesleys and the Holy Club at the University. “As once I affected to look more rakish, so now I strove to appear more grave than I really was.” But, as one sketch of his life remarks, “this … was like painting rotten wood: he was conscious all the time of the concealed corruption.

He tried another course. He denied himself every luxury; wore ragged, and even dirty clothes; ate no foods but those that were repugnant to him; fasted altogether twice a week; gave his money to the poor, and spent whole nights in prayer lying prostrate of the cold stones or the wet grass. But he felt it was all to no avail. He felt that there was something radically wrong in the very heart of him, something that all this penance and self-degradation could not change.”

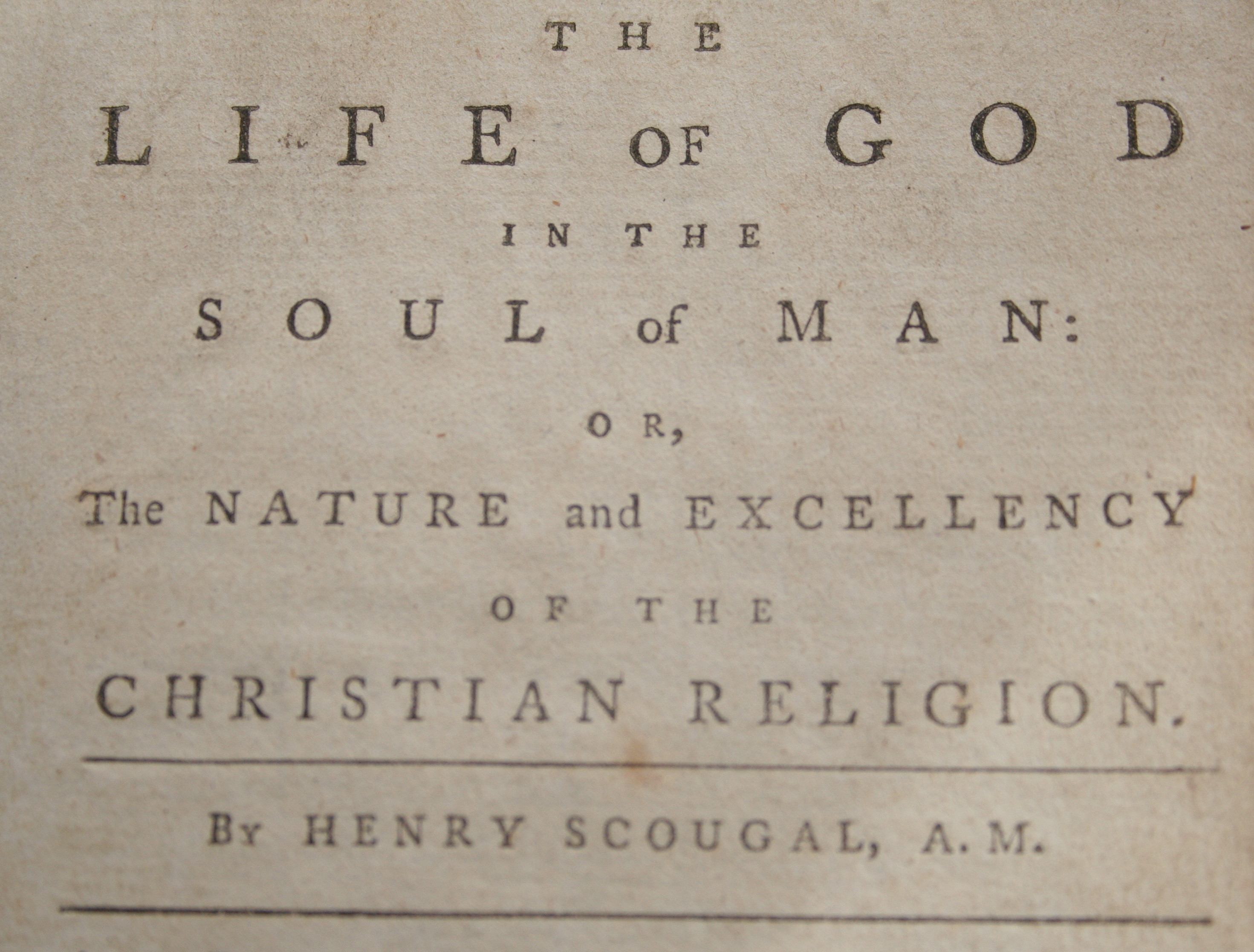

But God's means of changing Whitefield's heart was close at hand; it was in the form of a book – Henry Scougal's Life of God in the soul of Man. “I never knew what true religion was,” records Whitefield, “till God sent me that excellent treatise …” His feet were now turned in the right way, and we will follow those steps next time.

| This Page Title – George Whitefield (Part 1) The Wicket Gate Magazine "A Continuing Witness". Internet Edition number 96 – placed on line May 2012 Magazine web address – www.wicketgate.co.uk |